A Different Lincoln

December 21, 2009

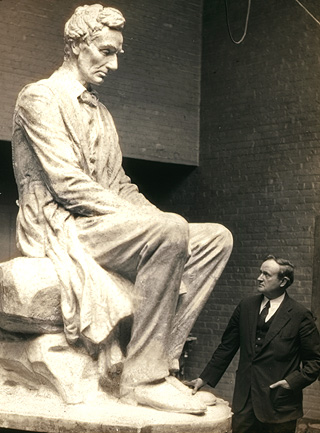

Anyone who has seen the Abraham Lincoln statue that anchors the Maxwell courtyard can’t forget it. But who is this Lincoln, and where did he come from?

If you are ever in Jersey City, New Jersey, set your GPS for the corner of JFK Boulevard and Belmont Avenue. But don’t turn onto Belmont. Go the other way, into a modest divided parkway heading west. What you find there may surprise you.

Sitting on a grand circular pedestal, centered in a granite exedra and flanked by low, inscripted abutment walls, is a statue of Abraham Lincoln. He is seated, pensive, gazing down toward the ground or toward you, the viewer, but seemingly so deep in thought as to notice neither you nor the turf. Except for its almond-brown patina, this could be the same Lincoln statue that sits in the grassy courtyard outside Maxwell Hall.

In fact, it is. Completed in 1930, this Lincoln is the original. Syracuse University owns the only full-sized bronze duplicate.

Each February, locals gather by the Jersey City statue to mark Lincoln’s birthday. Otherwise, the statue goes largely ignored. Its neighbors are nondescript, mid-sized apartment buildings that do not face it. Though noisy traffic rumbles by on JFK Boulevard, few cars turn into this parkway; sidewalks along its outer edges do nothing to encourage pedestrians to enter the median. In a nearby park, joggers and softball players are stumped when asked for directions to the statue.

In Syracuse, scarcely a day goes by when someone doesn’t approach the statue for a photo or just a better look. It is one of the University’s most photographed features and it is especially well-loved by citizens of Maxwell, who tend to think of it as their own.

The story of how it came to be is the story of zealous Lincolnites in the Garden State 80 years ago. The story of how it reached Maxwell is the story of an expanding university attempting to bolster its research holdings. And the story of why you always remember it is the story of the sculptor, James Earle Fraser.

The first coast-to-coast highway in America was called the Lincoln Highway, and stretched all the way to San Francisco. It was, however, a concept never fully realized. It was made up of pieces of other roads, and proposals to improve it nationwide never came to fruition. By the mid-1920s, the federal government had begun work on a system of national, numbered highways, rendering the Lincoln Highway insignificant. Still, when plans for a Lincoln statue in Jersey City were hatched, its location was proudly described as the eastern terminus of America’s only national highway. (Never mind that, as first conceived, the Lincoln Highway actually continued into Times Square.)

Jersey City is also the home of America’s most fervent Lincoln appreciation society. Its celebration of Lincoln’s birthday has occurred every year since 1866; no other Lincoln organization can rival that streak. In 1926, the society got caught up in a nationwide Lincoln-statue mania and launched a fund-raising drive. It eventually netted $75,000, including $3,500 in pennies and nickels from local school children. The statue would sit at an entrance to a large park on the western edge of town bordered by the Lincoln Highway. The park was immediately renamed for Lincoln, as well. (Lincoln Park has since shrunk, leaving the statue one block removed from its current entrance.)

In 1927, the New York Evening World reported that the Jersey City memorial committee had selected an artist. James Earle Fraser was the creator of the buffalo/Indian head nickel and End of the Trail, already an iconic piece of American sculpture, depicting a dejected, exhausted American Indian atop a similarly exhausted horse, possibly at the end of a forced exodus. End of the Trail was then sitting in San Francisco, near the western terminus of the Lincoln Highway.

“I don’t believe I have ever had a more enthusiastic feeling toward doing any monument than I have for this one,” Fraser reportedly told the committee.

In some respects, Fraser was an obvious choice. He was America’s leading sculptor of public, monumental art, responsible for the Alexander Hamilton at the federal Treasury Building; statues of Lewis and Clark and Thomas Jefferson in Jefferson City, Missouri; and a well-received statue of the inventor John Erickson in Washington, D.C.

But one wonders whether the good folks of Jersey City understood what they were buying. Many of Fraser’s statues are assertive and idealized, such as the brio-drenched Teddy Roosevelt outside New York’s Museum of Natural History. However, as End of the Trail demonstrates, Fraser was sometimes tempted to reach for subtler, darker attributes. Whereas the Lincoln Memorial in Washington (by Daniel Chester French) captures a noble, almost stolid president, apparently certain of his place in history, the Lincoln that Fraser envisioned is contemplative, worried, melancholic.

Fraser told the Christian Science Monitor, “I particularly wanted to make a sympathetic and human study of Lincoln. There are so many presidential Lincolns that I have hoped I might create something that would give an idea of his outdoor personality.

“In making a close study of Lincoln’s life and character,” the artist continued, “I have gained the idea that he did much of his thinking out of doors. He was brought up in the open and I believe he thought better outdoors. This is what I have tried to portray in the statue.”

According to some reports, Fraser had prepared a Lincoln five years earlier — a model viewed by an art patron who was considering Fraser for just such a commission. Fraser told the patron, “It is a thought I have had in mind for some time, and I believe a little different from any statue of Lincoln which has been produced.” However, the commission was never made and there is no description of the model to provide comparison with the Lincoln that came to be.

Through the years, some have claimed the statue depicts an actual moment. The story — allegedly related to Fraser by Lincoln’s former private secretary, John Hay — is that in the early days of his presidency, Lincoln would slip out the back door of the White House at dusk and climb a nearby hill, where he sat and considered his challenges. Historian F. Lauriston Bullard contested this notion, asserting that, even in the mid-19th century, no president could simply wander the hills outside Washington, searching for a nice place to sit and reflect on the day. Plus, that Lincoln would have a beard; Fraser’s is beardless.

In any event, Fraser created a Lincoln whose emotions are complex, whose visage is nuanced and deeply affecting.

On Flag Day, June 14, 1930, the governor of New Jersey, members of the Lincoln society, local politicians, a small delegation of Civil War veterans, and an audience of 4,000 dedicated the new statue. The governor called Lincoln “the wisest statesman our country has known.” Fraser was there, but did not speak. The event was noted by the Times and other New York City newspapers. And then, to a great extent, it was forgotten. Fraser went on to create other truly spectacular monuments in busier corners of the world. Lists of his greatest accomplishments rarely mention the seated Lincoln — or, as Jerseyites called him, Lincoln the Mystic.

James Earle Fraser was born in Minnesota in 1876 but his father, a railroad contractor-engineer, soon moved the family to Dakota Territory. Fraser met frontiersmen. Indian children were his playmates. For a time, the family lived in a railroad boxcar, the children sleeping on its floor wrapped in buffalo skins.

Fraser would thereafter describe the influence of his western upbringing on his art. He once wrote of observing the Indians in their villages, on hunting expeditions. “Often they stopped beside our ranch house; and camped and traded rabbits and other game for chickens. They seemed very happy until the order came to place them on reservations. One group after another was surrounded by soldiers and herded beyond the Missouri River. . . . I often heard my father say that the Indians would some day be pushed into the Pacific Ocean.” On another occasion he said, “I cannot say that the romance of the West attracted me as strongly then as later. I was oppressed with the sadness, the tragedy of it all.”

As a child, Fraser found chalkstone in a nearby quarry and began carving small sculptures. At age 15, he was sent to the Art Institute of Chicago; he first sculpted End of the Trail shortly thereafter. He next attended the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. He carried End of the Trail with him and it caught the attention of the acclaimed Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who became Fraser’s mentor. (It wasn’t until 1915, when End of the Trail was remodeled for the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, that it became famous.)

In 1902, Fraser set up shop in New York City. Among his first public commissions was a bust of Theodore Roosevelt for which Saint-Gaudens had been commissioned but could not execute. He sent his former student. Roosevelt was at first incredulous that the young Fraser was up to the task, but accepted Saint-Gaudens’ faith in him. The bust was considered a near masterpiece, capturing the Rough Rider’s pluck, and was moved to the Senate chamber.

Fraser’s first major public statuary was the Alexander Hamilton outside Treasury; for the rest of his life he would never be without a public commission. In addition to those already mentioned, Fraser sculpted the scenes, in relief, on the Michigan Boulevard Bridge in Chicago; various pediments for federal buildings, including Commerce; the two heroic figures in front of the Supreme Court; numerous medals; monumental allegorical figures such as Victory in Montreal; statues of Thomas Edison, Thomas Jefferson, and General George Patton (at West Point); and many, many others.

Some are straightforwardly heroic, such as the 60-foot-tall, perfectly erect George Washington prepared for the 1939 World’s Fair. Many included a dash of personality, such as a wise, benificent Ben Franklin sculpted in 1938 for Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute. Few, though, harbor the gravitas of either End of the Trail or Lincoln the Mystic. As the former somehow embodies the fate of the American Indian, Fraser’s Lincoln seems to capture, in the president’s troubled gaze, the daunting passage America faced on the cusp of civil war.

In the early 1960s, Syracuse University was completing its transition from the small Methodist liberal arts college it had once been to a teeming, multi-faceted research university. Chancellor William Tolley and others grew aware, though, that the research holdings of the University were not at the level of a great university. At the same time, the dean of the School of Art had instituted a “museum without walls” program by which more art would not only come to campus but find an audience in public spaces.

In 1963, Martin H. Bush, an instructor in Maxwell’s history department, was named assistant dean for academic development, with broad purview to track down papers and artwork. Over seven years, he approached dozens of accomplished figures — authors, actors, architects, politicians, generals, poets, artists, cartoonists, athletes — who, he imagined, might donate their papers, correspondence, and other ephemera to Syracuse University. There were many notable acquisitions at this time — for example, the Sacco and Vanzetti mural by Ben Shahn found on the eastern end of Huntington Beard Crouse Hall.

At the end of an astonishingly prolific career, James Earle Fraser had died in 1953. His wife, Laura Gardin Fraser, also a well-respected sculptor once the subject of a solo exhibition in Syracuse, then died in 1966. According to an account in the Westport (Conn.) News, plaster casts from the Frasers’ studio then began showing up at the dump in Westport, where the artists lived and worked.

The executor of their estate was Laura Fraser’s sister, Leila Sawyer. Bush somehow learned of the Frasers’ studio and soon arranged to have the entirety of both Frasers’ papers, books, photos, and more than 500 pieces of artwork come to SU, along with a $50,000 gift from Sawyer to help transport and maintain them. A portion of those materials was, in turn, sold to the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. (The plaster version of Lincoln the Mystic displayed there is the original from which the two bronzes were cast.) SU retains today the world’s most extensive collection of Fraser materials, including dozens of pieces of sculpture, many of which are studies or enlargement stages for eventual well-known works.

When the Fraser materials were acquired, someone decided to recast Lincoln the Mystic. Who and why is not entirely certain. Other pieces in the collection were being cast for a Fraser show at the Kennedy Galleries in New York; that may have been a factor. There was, as mentioned, a push to place public artworks on campus and, in Sawyer’s gift, a stipulation that SU help perpetuate the Frasers’ legacies. But no one knows for certain how it was decided that this piece — rather than, say, End of the Trail — would get a new home at Syracuse.

Dominic Iacono, current director of the SU Art Collection, says the decision to place Lincoln in front of Maxwell was almost certainly made by Chancellor Tolley — according to a story transmitted to Iacono by the then-dean of the School of Art. Tolley, who had an affinity for citizenship studies, also insisted Lincoln face outward, toward the community. (Others, including Maxwell Dean Stephen Bailey, would have turned it 90 degrees so that Maxwell Hall served as Lincoln’s backdrop.) A memo by Martin Bush, now in Syracuse University’s archives, claims the spot was suggested by University Vice President of Student Affairs Frank Piskor, an art enthusiast. Virginia Denton, who was early in her 40-year career on SU’s design and construction staff then, and who played a primary role in preparing the site, is unsure who first had the idea, “but there was no issue about where it should go.”

The statue was installed on December 13, 1968, with no fanfare. A truck and crane pulled up and the 2,700-pound, nine-foot-tall statue was set onto its concrete pedestal while a few passersby stopped to gawk. No one who was with Maxwell then remembers any ceremony — just a University-generated notice in the Daily Orange and local newspapers, in which the art critic Lorado Taft was quoted: “The statue marks the beginning of a great life. . . . It shows [Lincoln] in his younger days of poetic vision, of promise rather than fulfillment.” There Lincoln sits today, much admired but rarely discussed.

Iacono remembers sending museum-studies classes to visit the statue and the reports students would bring back. Many couldn’t even remember whether the statue was bearded, but “they would all talk about how he was a sad-looking person.”

When asked whether Fraser stands up as a great artist, Iacono thinks and qualifies his answer: “It’s great public art. . . . Fraser created a true monumentality in his art. Not many artists can do that.”

For a 1946 article in the journal of the American Institute of Architects, Fraser wrote, “The fundamental question arising, then, as we contemplate memorials to heroes of our day is: Will they cause the minds of men of generations yet unborn to remember?”

Few who have passed through the Maxwell School since 1968 ever forget the look on the face of their special Lincoln.

By Dana Cooke