Born of Fear

August 21, 2012

From Maxwell Perspective...

Born of Fear

Over a long career, Michael Barkun has studied the ways political, religious, and other social groups react to perceived threats.

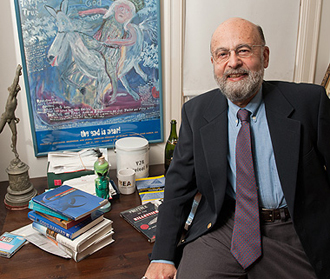

Michael Barkun, in his home office, with ephemera of the political fringe, conspiracy theorists, and UFO watchers.

In the aftermath of 9/11, when Washington policy makers revamped the nation’s strategies for domestic security, they were responding, in part, to new information about the threats posed by militant groups such as Al-Qaeda. But as Michael Barkun argues in his new book, Chasing Phantoms: Reality, Imagination, and Homeland Security Since 9/11 (University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming spring ’11), decisions that were made relating to homeland security were influenced by more than hard facts and on-the-ground intelligence.

“The book deals with the way in which we, in the sense of both a society collectively and its policy makers, think about evil, danger, and risk,” says Barkun. In examining the creation of the Department of Homeland Security and other major policy decisions, he describes the “fixation that we were going to be attacked using chemical and biological weapons even though there was very little evidence that either of those was going to be employed. An enormous amount of time and resources was expended on that, which I think says more about what frightened us in terms of our inner mental maps — what I talk about in the book as our landscape of fear — than what was really out there. So I think policy was driven more by what was in policy makers’ heads than by reality.”

“I think [post-9/11] policy was driven more by what was in policy makers’ heads than by reality.”

— Michael Barkun

Barkun, a professor emeritus of political science, has devoted his career to illuminating the beliefs and fears that guide people’s decisions and actions. Before the homeland-security study, his work focused primarily on political fringe groups — from millenarians who expect the imminent end of history to white supremacists, domestic terrorists, and conspiracy theorists of all stripes — resulting in books such as Religion and the Racist Right: The Origins of the Christian Identity Movement and A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America.

After the ill-fated 1993 clash with David Koresh and the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas, the FBI tapped Barkun as a consultant, seeking his insights into the connections among religion, violence, and political extremism. “They began to realize after Waco that one of the great gaps in their decision-making process was that they were not consulting with anyone who knew anything about religion,” Barkun says. “That’s one of the reasons Waco had been such a fiasco. They began to reach out to the academic community.”

Last summer Barkun retired after 45 years on the Maxwell School’s faculty, though he continues to teach in the Master of Social Science program. Reflecting on his work over the last several decades, Barkun notes how profoundly technology has changed the ways in which radical political movements and ideas are disseminated through society.

“When I was doing the research for Religion and the Racist Right in the late ’80s, early ’90s,” he recalls, “I was trying to get ahold of what had been put out by these very small right-wing extremist groups. There was only one place in the country where I could find it: the University of Kansas had probably the largest collection of right-wing extremist literature in the country. It was all print, and where do you go for it? You couldn’t go to a newsstand or a bookstore. . . .” Now, he adds, gesturing to his computer monitor, “it’s all there. No matter how weird it is, no matter how far out it is, no matter how extreme it is, it’s all on the Net.”

At the same time that technology has provided a new public platform for extreme political viewpoints and far-fetched conspiracy theories, these ideas have increasingly made their way into pop culture, Barkun notes. He cites the example of Dan Brown novels such as The Da Vinci Code, with its elaborate conspiracy-driven plot. “This is stuff that I would have previously had to find on the farthest reaches of the fringe,” Barkun says, “and there it is in a best-selling novel and soon a major motion picture at your local multiplex. So this material is now being mainstreamed through popular culture."

— Jeffrey Pepper Rodgers