Published

January 25, 2013

Related:

From Maxwell Perspective...

Published

The journal Chronos celebrates the best of undergraduate scholarship in the field of history — as judged by undergraduates themselves.

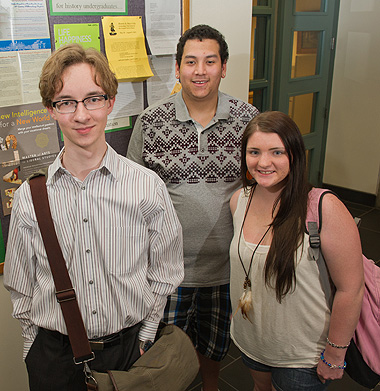

Chronos editors (from left) Davor Mondom, Max Lewis, and Ashlie Daubert outside the History Department office

Max Lewis, a junior from Ann Arbor, Michigan, can cite no concrete reason he volunteered to help edit his department's undergraduate journal. He's not padding his transcript; there are no plans for a PhD or the professoriate. He just really likes history.

"I found it interesting just to read other people's writing, and see how different people do it," he says. ". . . Sometimes you read something and you go, 'Wow. This is amazing. I can't believe this person goes to the same school as me.'" Other times, he says . . . well, not so much.

History is the rare department (the only at Maxwell) that sponsors a scholarly journal for undergraduates. It's called Chronos. The department funds the printing and provides a faculty advisor, currently Michael Ebner, an assistant professor. Ebner's impact, though, is intentionally restrained - help fire up the machinery each year, provide introductory advice on the process of peer review, and remain available in case questions or problems arise. "The sign it's going well," he says, at a time deadlines are nearing, "is that I've had very little to do with it."

The power lies with a five-person editorial board, headed this year by senior Davor Mondom, from Manlius, New York. Mondom is serious, contemplative, rational, all business. He is the only Chronos editor (at least among those we met) for whom history seems a likely career. (Having done his senior thesis on the Ku Klux Klan and labor movements, he'll be staying at Maxwell to begin a PhD in 20th-century American history.) More typical is Lewis, who, when home sick from school, watched the History Channel. "I just loved history my whole life," he says. Or fellow history major Ashlie Daubert, a senior from Hanover Township, Pennsylvania, and confessed high school "history nerd"; she participated every year in National History Day competitions. She's now interested in Vietnam War films and women's involvement in that war.

Papers considered for Chronos were first written for classes, received at least an A-minus, and then were nominated by their authors. Submitted papers are divvied up among editorial board members, using Google Docs and other modern means. Each editor reads five to seven papers, which cover a challenging array of topics. Mondom, for example, read papers on Facist movements in Great Britain, Napoleon and Robespierre, media coverage of the Kennedy assassinations, and Erie Canal boatmen, among others. Each editor approves any number of papers they deem worthy (typically, about a third) and reject the rest. Editors next return chosen papers to their authors with suggested revisions - grammar, better citations, maybe a request for better exposition. "What is meant by that? What are the implications?" Daubert explains.

“Were they able to interpret something from their research and bring something new to the table?”

— Chronos editor Ashlie Daubert

Beyond technical merit, a paper needs an idea, some sort of stance. "Were they able to interpret something from their research and bring something new to the table?" Daubert says. Or, as Mondom puts it, "Is this a good read?"

The process is enlightening. "You get a sense of how people write," says Mondom. "What people do right. What people do wrong. It's hard when you read your own paper. You don't have that objectivity."

By year's end, the finished product appears. A few printed copies are produced and sent to the authors and a few others. Electronic copies are made available to everyone else. This year's edition (Volume 7) contains 13 papers. Among topics: the civil rights movement and media, the demonization of cocaine in the 19th century, the Qing Emperorship, and Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor.

Ebner, the faculty advisor, says History has a rooting stake in Chronos containing really good papers, to serve as a showcase for the department. But the higher priority is that students did the work. Students made the decisions. "It's not about who knows better," he says. "It's their journal."

"I think it's important to have something to show for yourself at the end of a college career," says Daubert. She worked on Chronos this year partly to return a favor. She remembers when, last year, her own paper (on Vietnam War films) was published. "It was so cool to hold that in my hands in front of my parents. 'Look what I did.' I was so proud of it. And I thought, I want other students who work so hard to have that so-cool moment."

"Not many people get to say that, outside of class, they put together something huge like that," says Lewis. He wouldn't mind being editor-in-chief next year, and he is already recruiting history-major friends to get involved.

— Dana Cooke