Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion and Population Health

Population Health Research Brief Series

Gratitude as an Antidote to Anxiety and Depression: All the Benefits, None of the Side Effects

Mary Katherine A. Lee

May 2019

DOWNLOAD THE BRIEF [PDF]

View our other research briefs.

A gray cloud has been cast over the U.S. The epidemics of anxiety and depression have led to alarming declines in mental health. In fact, those who have been born since 1997 are reported to have the worst mental health of any current generation.1 Despite efforts among health care professionals, schools, and workplaces to address mental health issues, anxiety and depression remain pervasive public health concerns. Depressive episodes and anxiety attacks are all too common: school-aged children burst into tears over test scores, teenagers retreat to the “safety” of their phones and disengage with peers, college graduates struggle to pay off mountains of debt, and working-age adults face the overlapping stressors of work, family, and personal care. In some ways, these anxieties have become accepted as societal norms, and our collective need for instant gratification drives us to reach for pills to fix our problems.

Where are my “Happy Pills”?

Antidepressants are among the top three most prescribed medication classes in the U.S., with more than 260 million prescriptions each year.2,3 They are predominantly used to treat depression, but are also commonly prescribed for anxiety disorders. National trends are startling: According to the National Center for Health Statistics, the use of antidepressants jumped 65% from 1999 to 2014.2 Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health show continual increases of prescriptions for adults 18 and older who have problems with emotions, nerves, or mental health.4 Despite the steady rise in use of pharmaceuticals to treat anxiety and depression, these mental illnesses persist.2, 3, 5 But what if there was a way to “treat” anxiety and depression outside of the traditional medical model of pills?

Is Gratitude an Answer?

Emerging evidence shows there may be an alternative approach to battling anxiety and depression without the side effects of medication: Gratitude. Although more research is needed to explore the direct effects of gratitude on the alleviation of mental strife, there is strong indication that gratitude can improve symptoms for those suffering with anxiety and depression. Gratitude can be described in three ways: (1) as a trait - how naturally grateful is a person? (2) as a mood – how does gratitude fluctuate throughout the day? and (3) as an emotion – how fleeting is the feeling of gratitude after a positive interaction with someone?6

A person can feel gratitude in a variety of ways and intensities. There are many individual benefits one may experience by being grateful, including improved physical and psychological health, increased happiness, life satisfaction, positive mood, meaning in life, and quality of sleep.6,7 Trait gratitude is also linked to a more positive outlook on life, increased optimism and hope, and having a more positive interpretation of social situations.6,7 Grateful people tend to view adversity as an opportunity for growth, which can increase resilience.6 This positive perspective may prevent one from hyper-focusing on thoughts or experiences, which can lead to decreased depression and anxiety over time. Experiencing gratitude can also keep a person grounded in the present, leading to increased mindfulness.

People are more likely to be generous, kind, and helpful when they are grateful. This can strengthen relationships and improve workplace environments. Research suggests that grateful people “find, remind, and bind” to one another, as gratitude helps them find others who have the potential for a high quality relationship and reminds them of the positive aspects of their existing relationships. Feelings of gratitude can also bind people to their current partners and friends by encouraging behavior that will improve and prolong their relationships.6

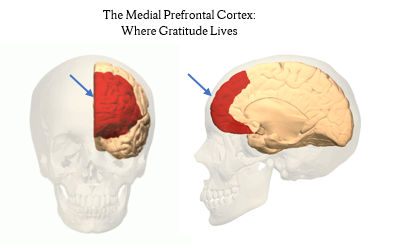

A Grateful Brain

The medial prefrontal cortex is activated when one experiences gratitude. This portion of the brain is located in the frontal lobe where the two brain hemispheres meet. The medial pre-frontal cortex is associated with socializing and pleasure, viewing others’ perspectives, empathy, and feelings of relief. Gratitude is connected to systems of the brain that regulate emotions and support stress relief, such as heart rate, arousal levels, and pain.6 When activated, these areas of the brain can boost positive emotions and protect against feelings of anxiety and stress, leading to an overall calmer mood.

Gratitude has No Negative Side Effects

Although medication is helpful for treating depression and anxiety in many people, gratitude can be an important supplement for improving symptoms. Evidence supports that gratitude interventions - activities that help a person focus on and increase gratitude - drastically minimize depression and improve socialization. There is growing use of gratitude interventions in clinical settings as an addition to psychotherapy. These interventions have long lasting, positive effects.8 Although medication is certainly necessary in some cases, gratitude interventions can offer safe and low-risk alternative approaches to battling anxiety and depression. Unlike medication, gratitude is simple, free, and maybe most important of all, has no negative side effects.

Give it a Try!

Here are four popular gratitude interventions to try:

- Gratitude Journal: Reflect on and write down 3-5 things for which you are grateful 2-4 times a week.

- Three Good Things: Similar to the gratitude journal, reflect on and write down 3 things you are grateful for and/or 3 things that went well. You should also include the reasons behind those three good things. Do this 2-4 times a week.

- Mental Subtraction (Writing Optional): Imagine what your life would be like if a positive event had not happened.

- Gratitude Letter: Write a letter to someone to whom you are grateful but have never explicitly told. Reading the letter out loud to the person or having them read it will help strengthen your relationship with them.

Endnotes

- American Psychological Association (2018). Stress in America: Generation Z. Stress in America™ Survey.

- Pratt, L.A., Brody, D.J., & Gu, Q. (2017). Antidepressant use among persons aged 12 and over: United states, 2011–2014. NCHS data brief, no 283. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

- Olfson, M., & Marcus, S.C. (2009). National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(8), 848-856.

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD.

- Rhee, T.G., Schommer, J.C., Capistrant, B.D., Hadsall, R.L., & Uden, D.L. (2018). Potentially inappropriate antidepressant prescriptions among older adults in office-based outpatient settings: National trends from 2002 to 2012. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 45, 224-235.

- Allen, S. (2018, May). The Science of Gratitude. Retrieved March 8, 2019, from https://ggsc.berkeley.edu/images/uploads/GGSC-JTF_White_Paper-Gratitude-FINAL.pdf.

- Fox, G. (2017, August 4). What Can the Brain Reveal about Gratitude? Retrieved March 11, 2019, from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/what_can_the_brain_reveal_about_gratitude

- Wood, A.M., Maltby, J., Gillet, R., Linley, P.A., & Joseph, S. (2008). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 854-871.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Shannon Monnat and Alexandra Punch for their help revising earlier drafts.

About the Author

Mary Kate Lee is the Program Coordinator for the Syracuse University Lerner Center (mlee77@syr.edu).